1960s-1970s: In and Out of Sight

By the 1960s, Boxer was a big deal on campus. But strangely, he was not the school's official mascot. That honor went to the "Badger," which the university's administration had adopted in 1921. Students were ready to give Boxer a higher profile, though. They had already named several campus institutions after him, like the "Boxerettes" women's service organization, which helped run social events and elections. As early as 1963, students and alumni were calling for the retirement of the Badger in favor of their own grass-roots symbol.

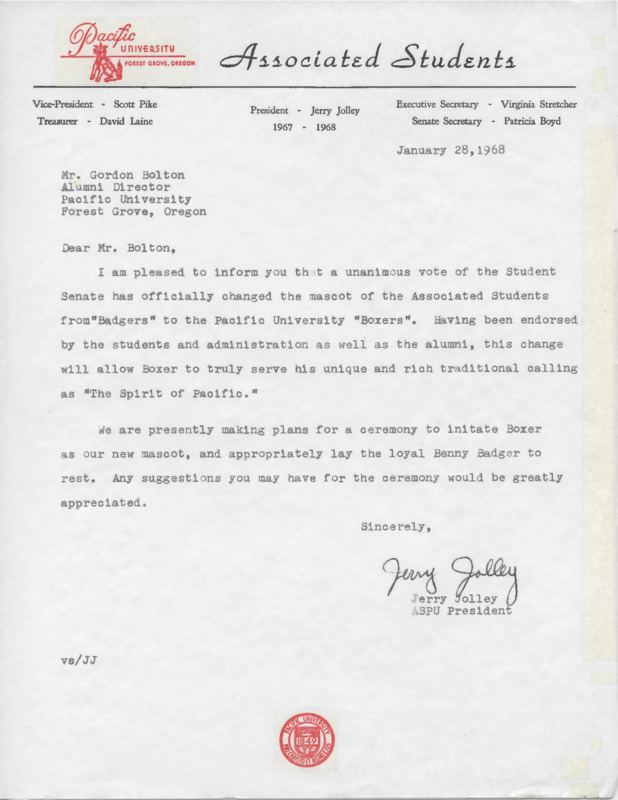

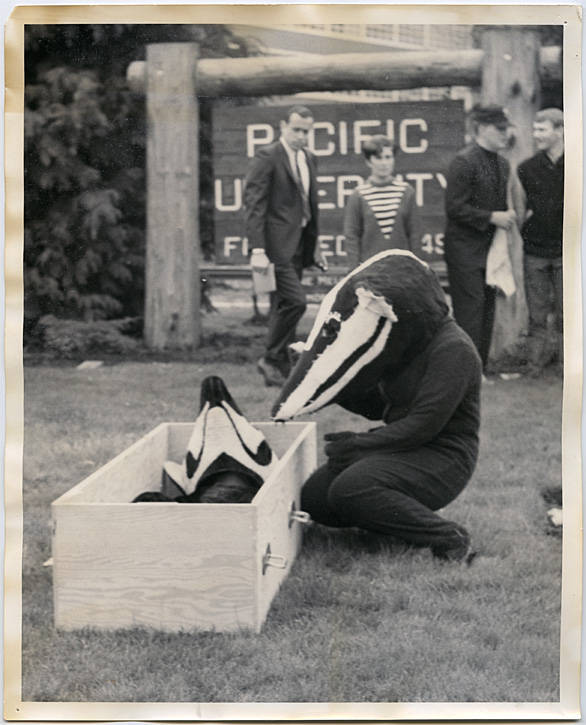

In 1968, the Student Senate voted unanimously to make Boxer the official mascot. Badger was symbolically buried in a ceremony not long afterwards. You can still see the last Badger mascot costume today: it is on display in Pacific's museum on the second floor of Old College Hall.

Soon afterwards, members of the Alpha Zeta fraternity brought Boxer along to meet Richard Nixon while he was on the campaign trail in Oregon. Photos of this event have been among the most popular images of Boxer of all time. (For more on this event, see: How did Nixon meet Boxer?)

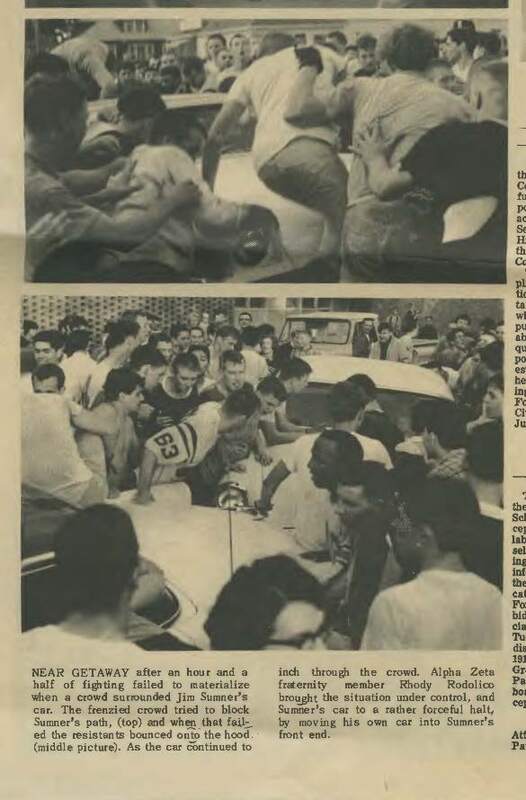

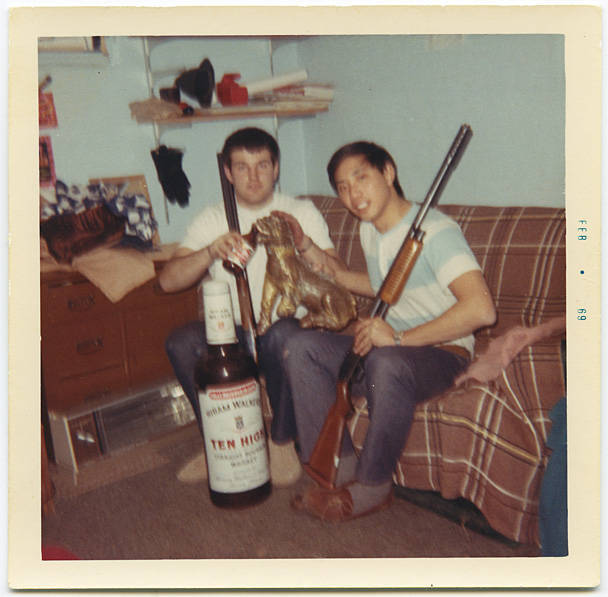

Meanwhile, the Boxer Toss tradition was becoming rowdier every year. Huge crowds of students were fighting over Boxer whenever the statue appeared. In one of the last Tosses, student Pat Truax -- a future mayor of Forest Grove -- arrived in the middle of Trombley Square one afternoon, riding in the trunk of a car and holding Boxer. When he threw out the statue, a swarm of desperate students descended upon it. (See the video of this Toss and more about the Boxer Toss tradition here.)

Fighting, dangerous car chases, and high spirits around Boxer infected the campus every time a Toss occured.

While most Pacific students saw the Boxer Toss tradition as pure fun, by the late 1960s a minority began to see it as a glorification of violence and as a distraction from more important issues. The all-out brawls over Boxer were happening against a backdrop of social change and political struggles concerning the war in Vietnam. Racial issues added to the tensions. At the time, Pacific University was among the most racially diverse campuses of any private college in the Pacific Northwest. Around 15% of the student body was Asian-American or Pacific Islander; around 10% were Black. While many of these students felt welcomed and integrated into some parts of Pacific's culture, they had to deal with prejudice and ignorance as well. Black, Asian and Pacific Islander students wanted their own social groups to support their specific needs. Some joined Nā Haumāna O Hawai‘i; others joined the Black Student Union. The Black Student Union in particular became a focus for political disagreements on campus, as its members loudly voiced calls for greater equity and inclusion. (For more perspectives on Black student experiences at this time, see: "Arriving Alone, Joining Together," Pacific Magazine, 2018; or Donna Maxey Easter's Oral History of her time as an African-American student at Pacific in the late 1960s.)

With all this in mind, it is not surprising that the disappearance of Boxer in 1969 quickly got politicized.

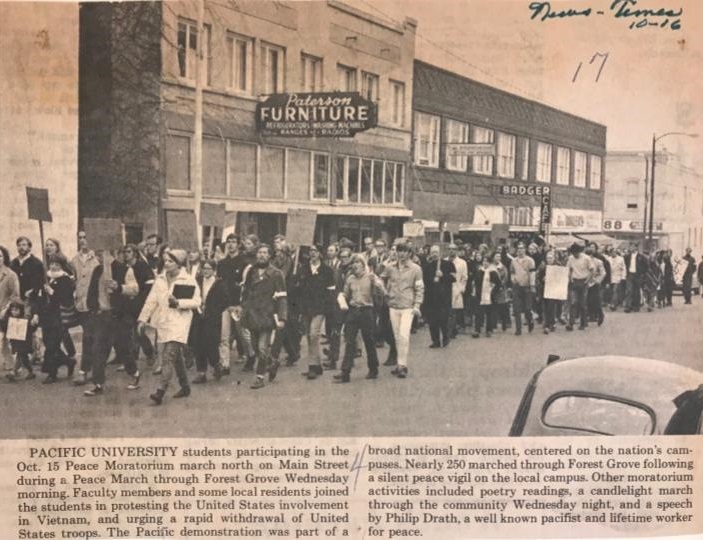

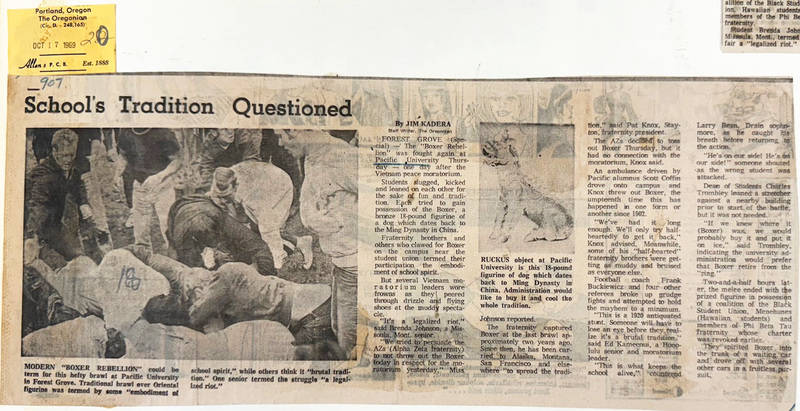

The last Toss of the original Boxer statue occured on October 16, 1969. This was just one day after anti-Vietnam activists at Pacific had organized a "Peace Moratorium" march. The proximity of the two events led to added tension between student groups. "It's a legalized riot. [...] We tried to persuade the AZs to not throw out the Boxer today in respect for the moratorium yesterday," student activist Brenda Johnson told The Oregonian. "Someone will have to lose an eye before they realize it's a brutal tradition," said Ed Kameenui, another student activist. But Alpha Zeta's leaders did not see a conflict, saying that there was no connection between the two events. While the fraternity members may have seen the Toss as a politically neutral fun and spirited event, it was clear that not everyone felt that way.

After the 1969 Toss, Boxer disappeared from public view. Boxer had been hidden before, sometimes for years at a time. But this time, rumors about its whereabouts turned ugly. A Black student was thought to have won possession of it at the end of the last Toss. Fraternities had controlled Boxer for at least a decade prior, so many students assumed that it wasn't just an individual student holding Boxer: they believed that the Black Student Union (BSU) was in control of the university's most powerful symbol.

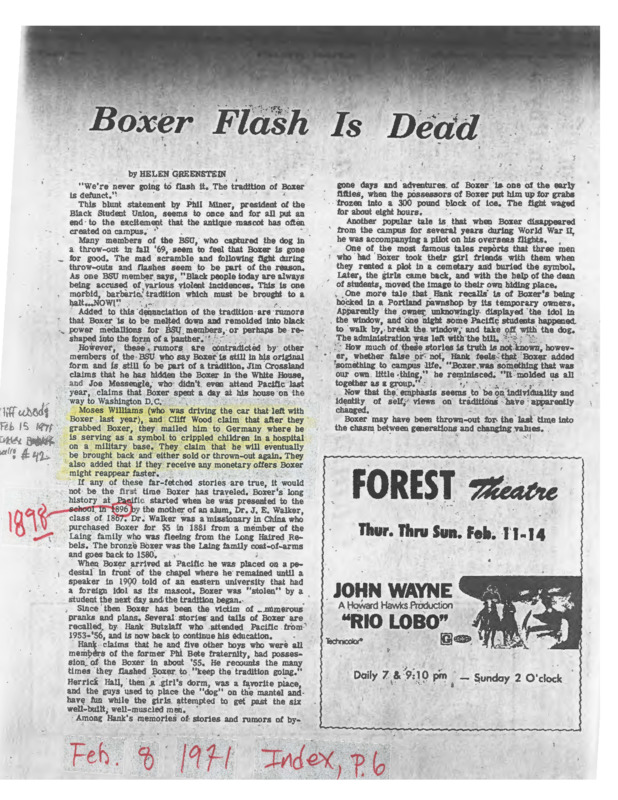

Rumors spread that the BSU was intentionally keeping Boxer away from campus in order to make a political point. Some members of the BSU played into this, with one declaring to the campus newspaper, "We're never going to flash it. The tradition of Boxer is defunct." Another member was quoted as saying: "This is one morbid, barbaric tradition which must be brought to a halt ... NOW!"

The truth was that the BSU did not have Boxer, either. But who did have it?

More rumors flew. Some said Boxer had been dropped off the Golden Gate Bridge. Others said it had been melted down. Some said it had been moved to another country, or was simply sitting in someone's basement, forgotten.

As it turned out, Boxer's location would not be known for another 55 years.